In Washington, D.C., it is an article of faith that “the cover-up” is always worse than the crime. President Trump has upset that notion.

Up to now, the conventional wisdom had a lot of empirical grounding: There is no evidence, for example, that Richard Nixon knew of the Watergate break-in in advance. He resigned from office because he covered up a “third-rate burglary” that he had no role in planning or carrying out.

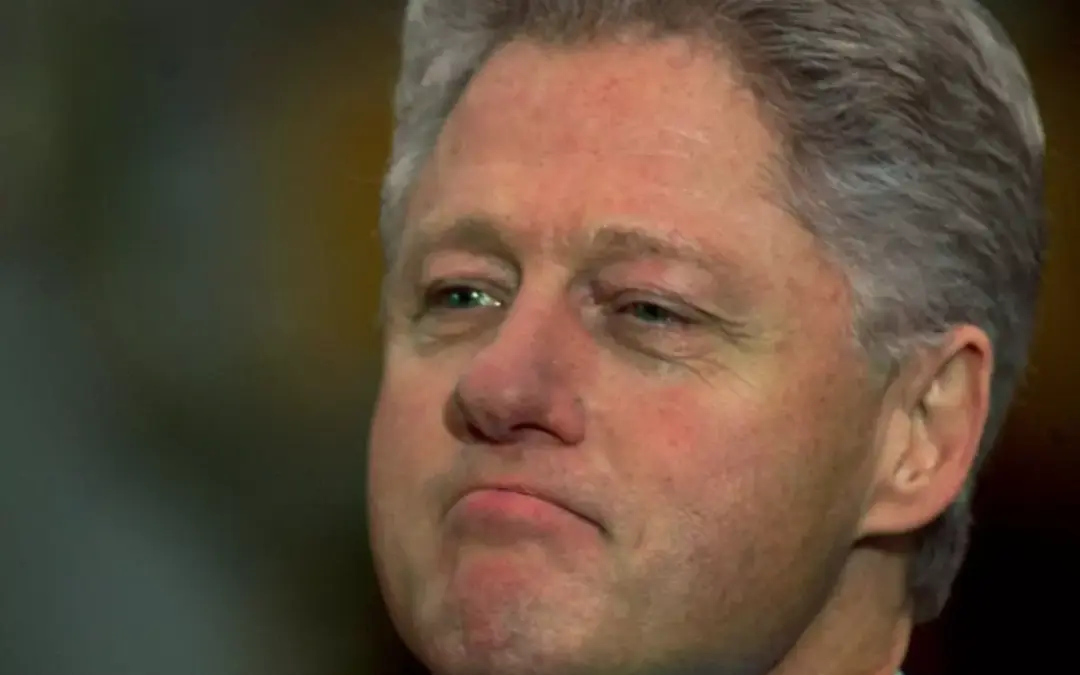

Likewise, Bill Clinton engaged in a tawdry affair with intern Monica Lewinsky — conduct that, in our #MeToo era looks more questionable than ever. But his impeachment was not for bad behavior. Rather it was for his perjury and obstruction of justice in concealing that affair from the American people — and, in the end, from the federal courts. Until recently Donald Trump’s most egregious offenses stemmed primarily from his multiple acts of obstruction of justice in the Mueller investigation of his connections to Russia.

Now, however, everything is different. President Trump is the subject of an impeachment inquiry that deals directly with concerns about his personal official conduct. And the difference between a cover-up and a crime is significant.

To understand this, think of the Trump impeachment investigation in comparison to the investigation of Clinton.

I was senior counsel in the Office of the Independent Counsel during the Clinton investigation, and I don’t want in any way to minimize the significance of the allegations against him. But in that case, Lewinsky’s contact with Clinton was consensual, however morally reprehensible on the president’s part. It was Clinton’s decision to obstruct justice by lying about his conduct under oath that led to his impeachment charge. In the end, he was not removed from office, but he was held in civil contempt by the federal judge who presided over the case in which he lied under oath.

Clinton’s conduct undermined his office to the extent that we demand honesty and adherence to the rule of law from all citizens and especially from the president. Clinton’s frivolous claims of executive privilege as he attempted to avoid exposure of his affair undermined his presidential authority. But Clinton’s misconduct, while far worse than a simple “fib about sex,” did not directly involve the misuse of his presidential authority. That abuse occurred only in his attempts to cover up his actions.

Trump’s acts in soliciting Ukrainian interference in the political affairs of America are very different. His actions implicate him in the personal abuse of presidential authority.

First, there is Trump’s use of his office to solicit an investigation of the son of his political opponent. This was a misuse of authority on several levels. At its most basic, the president should never be in the position of soliciting an investigation of an American citizen by a foreign nation. If a citizen has committed allegedly criminal acts, then the proper response is to ask the FBI to investigate.

Second, it is a federal crime to solicit or receive a thing of value from a foreign national in aid of a federal election. According the head of the Federal Election Commission, an investigation of your political opponent (and receiving the resulting “dirt”) is a thing of value under the law. So, by asking for an investigation of Biden, Trump has directly committed acts that likely rise to the level of a high crime or misdemeanor.

All this is true even before we consider whether the president’s withholding of political support and military aid as leverage to compel Ukraine’s assistance with the Biden inquiry constitutes a quid pro quo. If you add that context —the president withholding foreign aid funds authorized by Congress to advance his own political interest — the abuse of authority becomes even more palpable.

And therein lies the essential difference distinguishing the Trump case from the Clinton matter. Today, unlike in 1998, the abuse of public trust is directly tied to the president’s conduct of America’s foreign affairs. It is precisely the sort of foreign entanglement that deeply concerned our founders.

James Madison feared that a president might “betray his trust to foreign powers.” Another of the founding fathers, Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, at first opposed including an impeachment clause at all, but later agreed to because he realized we needed recourse for “the danger of seeing the first Magistrate in foreign pay.”

In the past, we have faced presidential impeachments where the cover-up was the abuse. Sadly, we have now reached a place where a president’s official use of his authority is what’s in question. Each impeachment sets a precedent that resonates through history. Those who are engaged in evaluating President Trump’s behavior should proceed cautiously, lest they set a precedent that approves the use of presidential authority for personal gain. That unfortunate choice would leave a stain on the fabric of society for a long time to come.

Paul Rosenzweig was senior counsel to Kenneth Starr in the Whitewater investigation and a deputy assistant secretary of Homeland Security in the George W. Bush administration. He is a senior fellow at the R Street Institute and manages the cybersecurity consulting firm Red Branch Consulting.