Table of Contents

- Net Neutrality: Reining in Innovation

- Internet Governance: Past, Present, and Future

- Regulatory Barriers to Online Commerce

- Protecting Internet Commerce from Undue Tax Burdens

- Copyright and the Internet: Getting the Balance Right

- The Intersection of Internet Freedom and Cybersecurity

- E-mail Digital Privacy

In the space of barely 20 years, the world has been changed immeasurably by the advent of the Internet and other communications technologies. These breathtaking advances have not only expanded the economy but have improved the quality of life for billions of people around the globe. For the first time in world history, information is available to individuals at literally the touch of a finger, letting them keep in touch with friends and family, giving them access to goods and services from around the globe, and enabling them to participate in civic affairs.

This revolution in human affairs is a success story of free markets. Although some of the initial technologies were created as part of a Defense Department research project, the Internet long ago shed its government links and has thrived as a largely unregulated network, harnessing the energy and creativity of countless private individuals and firms. No central authority dictates which services are provided on the Web, which technologies are used, or what kind of content will be available. The result is an innovative and competitive cornucopia of offerings.

The advent of the Internet has been as rapid as it has been transformative. In 1983, a Harris poll estimated that some 1.4 percent of Americans used the Internet.[1] By 1995, Pew Research found that 10 times as many Americans had Internet access—which was still a relatively paltry 14 percent. Three times that number—42 percent of Americans—still had not heard of the Internet in 1995.[2] Today, by contrast, close to 90 percent of Americans are online, and over 70 percent go online from home on a daily basis.[3]

It has become virtually impossible to imagine a world without an Internet. Instant access to information—from stock quotes to sports scores to the answers to bar bets—is taken for granted. Getting and staying in touch with friends and business partners has become easier, as individuals connect almost effortlessly with friends around the globe, and from long ago, on social networks. This instant and ubiquitous communication and information has also transformed political dialogue—helping to upend dictatorships abroad, and energizing political debate at home.

The common product of these transformations has been more opportunity for freedom—political freedom in the public square, economic freedom in the marketplace, and social freedom in the community.

But these changes are not universally welcomed. The disruptive force of the Internet is a threat to those who have enjoyed unchallenged political power and economic rents from the status quo ante. This has led to attempts by governments around the world to limit its use, and forestall the changes that it makes possible.

The trend is disturbing. In its 2014 survey of the state of Internet freedom around the globe, Freedom House records the fourth straight year of declining freedom on the Net. From 2013 to 2014, Freedom House found 41 countries passing or proposing online-speech restrictions and arrests related to online political speech in 38 countries.[4] Moreover, it reports continued widespread blocking and filtering of online content by governments, as well as government-sponsored cyberattacks against other countries’ governments and businesses.

Infringements on the Internet are not limited to the world’s dictatorships. The European Union, for example, recently required search engines, upon request, to remove links to categories of personal information, such as prior bankruptcies, which courts deem no longer relevant or lack a compelling public interest meriting disclosure—in effect forcing search engines, such as Google, to censor content.[5]

The United States has largely escaped such direct infringements of political rights and freedom of speech on the Web. But Americans face threats of different kinds, ranging from foreign governments trying to impose global-governance rules to domestic regulators trying to limit the economic freedom to innovate and serve digital consumers.

This report examines seven areas of particular concern:

- Federal “network-neutrality” regulations. Rules adopted by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in February 2015 bar Internet access providers from prioritizing the content that is sent through their networks. This ban limits the ability of Internet service providers (ISPs) to innovate, which limits economic freedom, to the detriment of the Internet and its users. In addition to activities clearly prohibited, the new rule also gives the FCC vast discretion. As a result, critical decisions about what practices will be allowed on the Net will be left to the subjective judgment of five unelected FCC commissioners.

- Global Internet governance. Many nations, such as China and Russia, have made no secret of their desire to limit speech on the Internet. Even some democratic nations have supported limiting freedoms online. With the U.S. government’s decision to end its oversight of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the private, nonprofit organization that manages name and number assignments on the Internet, these countries see a chance to fill the vacuum, and to use ICANN’s Internet governance role to limit expression on the Web.

- Regulatory barriers to online commerce. The Internet is a true disruptive force in commerce, challenging inefficient ways of business. Often, these challenges conflict with anti-consumer laws that protect middlemen and others with a stake in older, costlier ways of doing business. These harmful laws have eroded in many cases, but have not been erased from the statute books.

- Internet taxation. Sales and other taxation also create regulatory barriers to online commerce. Some politicians and state tax collectors are pushing Congress to pass legislation that would allow state governments to force retailers located in other states to collect their sales taxes. They say they want to equalize the tax burdens between so-called brick-and-mortar retailers and their online counterparts. But instead of eliminating differences, the proposal would create new disparities and impose new burdens, as sellers struggle to deal with the tax laws of some 10,000 jurisdictions and 46 state tax authorities.

- Intellectual property. The freedom to create without fear that one’s creation will be appropriated by others is fundamental. At the same time, overly restrictive laws limiting the use of intellectual property erodes other freedoms, not least freedom of expression. The challenge to lawmakers is to balance these two opposing values, to protect intellectual property without undue limits on its fair use or on third parties.

- Cybersecurity. To enjoy the freedoms made possible by the Internet, a certain amount of security is needed to protect it from cyber theft, vandalism, and other criminal threats. This security cannot simply be achieved by government mandates. Government should remove barriers that hinder private-sector efforts to protect online networks.

- Digital privacy. Under current law, communications by Americans via electronic networks enjoy less protection than a letter sent by mail. Government does have a legitimate interest in viewing private communications in limited circumstances in order to apprehend criminals or terrorists and to protect security. But to do so, the government should be required to obtain a search warrant for each case, holding it to the constitutional standards that protect other communications, such as mail.

James L. Gattuso is Senior Research Fellow for Regulatory Policy in the Thomas A. Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.

Net Neutrality: Reining in Innovation

James L. Gattuso PDF

For an issue that has been debated for more than 10 years, “net neutrality” oddly remains a mystery to most Americans. One reason behind the unfamiliarity is the unusually technical nature of the subject matter, which lies at the intersection of engineering, economics, and law. Another is that the rhetoric of net neutrality has confused more than enlightened. Supporters tout the imposition of net neutrality constraints as strengthening Internet freedom; they claim that shackling providers of Internet access—Internet service providers (ISPs)—will increase the freedom of content providers to innovate and grow. But the real effect of these newly adopted rules will be quite different. Not only will the economic freedom of ISPs be limited, but so, too, will the freedom of the very providers of content who will find their options limited by a more slowly growing Web. In the end, it is the everyday consumers who will suffer the most, enduring inadequate service and an inability to choose plans that best suit their needs. The biggest winner will be the government, which will find itself with unprecedented discretion over how this network operates.

The term “network neutrality” refers to the principle that Internet service providers (such as Verizon and Comcast) that serve end users should treat all communications that travel over their networks the same way. The concept is based on a network-engineering rule of thumb but had never before been enshrined in a governmental rule or regulation. In fact, in the early 2000s, the FCC specifically declared, in a series of rulings, that broadband Internet service was not a “telecommunications service,” and thus not subject to common-carrier rules that bar variations in rates and services. Unlike traditional telephone companies and electric utilities, broadband providers would be free to establish their own business models in the marketplace.[6]

Those findings made sense. Broadband service was, and is, no staid utility. It is a dynamic and growing market with a thin line between a successful investment and failure. Differentiated offerings, such as discounts and priority-service plans, are common in such markets. And the market for broadband is competitive. Despite high capital-investment costs, the ISPs enjoy no monopoly, with two or more major players competing in almost every service area, limiting the prospect for market abuse.

Nevertheless, at the same time that the FCC declared that digital-subscriber-line (DSL) broadband was not a “telecommunications service,” it adopted a set of “non-binding” guidelines articulating neutrality principles in 2005. In 2008, the FCC ordered Comcast to stop alleged violations of the principles. Two years later, however, a federal appeals court ruled that the FCC could not enforce the non-binding principles.[7]

In December 2010, the FCC returned to the issue of net neutrality, adopting formal rules limiting how ISPs could handle Internet traffic, and broadening its claim of authority. These “open Internet” rules, as the FCC dubbed them, banned consumer wireline (DSL and cable modem) broadband providers from “unreasonably discriminat[ing] in transmitting lawful network traffic,” and “block[ing] lawful content, applications, services, or ‘non-harmful’ devices.”

Verizon, claiming that the FCC lacked jurisdiction over broadband service, soon challenged the new rules in court. As was the case in 2010, the FCC’s rules were slapped down in January 2014. Specifically, the court found that the regulations imposed on the ISPs were, in effect, common-carrier regulations. Since the FCC had previously ruled that the broadband service providers were not “telecommunication providers,” the FCC was barred by law from imposing common-carrier regulations on them.[8]

In February 2015, the FCC made its third and by far broadest bid to impose network-neutrality rules. By a 3-to-2 vote, the agency reclassified Internet service as a common carrier service, allowing it to regulate ISPs as public utilities.[9] Using this just-declared regulatory power, it then banned ISPs from blocking or slowing down transmissions, and from engaging in “paid prioritization” by offering premium or discount services. This decision also applied to wireless broadband service, which had been exempted from previous attempts to regulate Internet providers.

In addition, the FCC imposed a catchall “general conduct” rule, banning any ISP activities that “unreasonably interfere with or unreasonably disadvantage” the ability of consumers to receive—or content providers to deliver—content, applications, services, or devices of their choice.

What this means in practice is anybody’s guess. The FCC says it will enforce this provision on a case-by-case basis, maximizing its flexibility and reducing its transparency. This action will keep regulated enterprises in the dark about what is allowed and what is banned.

The general conduct rules spell an end to what has been called “permissionless innovation” by Internet providers.[10] No longer will ISPs be free to pursue new ways of handling content or new services for Web users. Every innovation will be under a cloud until approved by regulators in Washington.

Advocates of FCC network-neutrality rules argue that such restrictions are essential in order to protect consumers and providers of Internet content from ISPs who otherwise would block content, such as websites and applications, which compete with their own, or discourage innovation by charging undue fees for delivering content to users.

But this sort of behavior is unlikely to occur due to competitive checks on ISP market power. In fact, there has been only one case in which an ISP has blocked Internet content to its own advantage, and that ISP—a rural telephone company in North Carolina—quickly reversed its stance under pressure by the public and the normally slow-moving FCC.

Other claimed instances of anti-consumer activity have, on closer inspection, turned out to be pro-consumer.[11] For instance, in 2008, Comcast was alleged to be “throttling,” or slowing down, users of BitTorrent peer-to-peer (P2P) services. But for all the controversy, there was never any indication that Comcast took the action to favor itself. Rather than block competition, the “throttling” was to prevent P2P users from slowing network speeds for other users.

Anti-competitive activity by ISPs is rare for a reason. Economically, the ISPs would be shooting themselves in the foot should they block or discriminate against popular content. Their interest is in getting more content over their networks, not less. Should they try, competitors would be happy to snap up the displeased consumers.

Lastly, even in the event that competition fails to protect consumers, the antitrust laws already on the books provide strong backstop protection against anti-competitive behavior.

A primary concern expressed by advocates of regulation is that ISPs would speed up or slow down traffic on their networks for a fee, a practice known as “paid prioritization.” This, they say, would create the equivalent of “fast lanes” on the Internet, unfairly relegating content providers with fewer resources to slower, inferior Internet service.

This claim is nonsense. There is nothing wrong or unusual about differentiated prices. Every well-functioning market has premium pricing and discounts. Such variations are not a barrier to new competition or new services; in fact, they enhance them. One can imagine, for instance, if the same rule were applied to package delivery, banning expedited service and requiring all deliveries to be made in the same time frame. Not only would consumers be worse off, but online retailers—especially new entrants to the marketplace—would have one less dimension in which to distinguish themselves from their rivals.[12]

In any case, no ISP to date has announced plans to adopt a simple “fast lane” pricing system. Instead, the marketplace has been developing a variety of innovative service plans that promise to be a boon to competition and consumers.

MetroPCS, for instance, a smaller, low-cost wireless provider now owned by T-Mobile, attempted to shake up the mobile market in 2011 by offering unlimited wireless access to YouTube on its introductory $40-per-month price-tier service for no additional cost. MetroPCS had no special relationship with YouTube, but it “saw that YouTube is one of the main ways that our customers get multimedia content and we wanted to make sure that content was available to them.”[13]

The company drew the ire of pro-regulation groups, such as Free Press, which described the plan as “a preview of the wireless future in a world without protections,” and accused the company of “anti-consumer practices.”[14]

But MetroPCS was helping consumers. In fact, no one was prevented from enjoying other services. Access to streaming video, voice over IP (VoIP), and other data-intensive services was not only available on the company’s higher-priced tiers, but part of plans offered by MetroPCS’s many larger rivals. As economist Tom Hazlett of Clemson University notes,

[MetroPCS] customers were mostly price-sensitive cord-cutters who had little use for the bells and whistles of larger carrier plans, especially at higher price points. MetroPCS’s plan was poised to bring wireless data to this market segment. But instead it found itself facing the threat of agency action because its plan did not match the Federal Communication Commission’s preconceived notion of what the wireless broadband experience should be.[15]

Similarly, T-Mobile in June 2014 launched a program it calls Music Freedom, which provides users with access to various streaming music apps, such as Pandora, Spotify, iTunes Radio, and Rhapsody, without contributing to their monthly data allotment. Under the arrangement, T-Mobile would not charge the music services for the data-cap exemptions.

However, even this would potentially be barred by neutrality rules. Supporters of FCC regulation objected to this freedom and accused T-Mobile of violating net-neutrality principles. Chris Ziegler of Verge, for instance, called the plan “really, really, really bad,” asking, “What’s to stop [T-Mobile] from using data-cap exemptions as a punitive measure against content providers that aren’t on good terms with T-Mobile (or its parent company Deutsche Telekom)?”[16]

By this reasoning just about any discounting of consumer products or services could also be condemned. Once again, the threat of net-neutrality regulation was being used not only to block potential price breaks for consumers, but also to stymie competition from smaller players in the marketplace.

The new FCC rules do not stop here. As noted above, the agency has also established a “general conduct” rule, banning activities that “unreasonably interfere” with Web access by consumers or “edge” providers (a term including firms ranging from Google to Netflix to the smallest app maker). This new offense is only vaguely defined by the FCC, leaving providers uncertain about what is prohibited, and therefore dependent on regulators for clearance for any innovative activities that might hurt their competitors.

As far-reaching as these new rules are, they may be only the beginning. The interconnection of ISPs and “backbone” carriers (which transport content from the edge providers to the ISPs) has successfully operated without government regulation for a long time. But, Netflix now maintains that this, too, is a net-neutrality issue, asking the FCC to ban ISPs from charging to interconnect.[17] The result would be a boon for Netflix—which is responsible for some 34 percent of peak Internet traffic in the United States.[18] Instead of paying for the burdens placed on ISP networks, the cost would be borne by ISPs and their customers—whether they use Netflix and similar services or not.

Other forms of neutrality are sprouting up as well. Google, initially one of the strongest corporate proponents of network-neutrality rules for ISPs, has found itself beset by claims that a similar concept of “search neutrality” should govern search engine results. These would require search engines to display results from user queries in a non-discriminatory way. (Never mind the fact that, by their very nature, search engines differentiate content, providing more prominence to results that users are expected to value more, rather than in random order.)

In 2011, after a lengthy investigation, the Federal Trade Commission declined to pursue an antitrust case against Google based on search neutrality. But European competition-law officials recently launched a case against Google alleging just that.[19] The push for broad search-neutrality rules, however, is not over, and may be intensified with the FCC’s adoption of neutrality rules. Some, in fact, have speculated that such rules could even be applied to other Internet firms, such as Amazon, which openly offers higher placement in search results for pay.[20]

App writers, too, could be targeted for regulation under neutrality rules—at least if Blackberry CEO John Chen has his way. In a January 2015 blog post, Chen argued that net-neutrality regulations should be extended to makers of applications for wireless devices.[21] Under such “application neutrality,” an app made for Android or Apple phones would also be required to work on a Blackberry. Such a rule would be a natural extension of the neutrality principle, and, coincidentally, would also be a boon to Blackberry’s flagging fortunes.

The FCC’s adoption of net-neutrality rules was a substantial loss for advocates of Internet freedom. The issue is not yet settled, however, as the rules face challenges in Congress and in the courts. At the same time, policymakers should resist calls to expand the neutrality “principle” to other patches of the Web, which would only compound the loss of freedom.

Internet Governance: Past, Present, and Future

Brett D. Schaefer PDF

Over the past 25 years, the Internet has gone from a relatively unknown arena populated primarily by academics, government employees and researchers, and other technical experts into a nearly ubiquitous presence that contributes fundamentally and massively to communication, innovation, and commerce. In 1990, only about 3 million people worldwide—0.05 percent of the world’s population—had access to the Internet, of which 90 percent were in the U.S. and Western Europe.[22] Between 2000 and mid-2014, the total number of Internet users worldwide grew from 361 million to more than 3 billion—more than 42 percent of the world’s population.[23] This growth has been global and, in recent years, particularly rapid in developing countries.[24] Thus, it is unsurprising that, as the Internet has expanded in importance both as a means of communication and as a catalyst for entrepreneurship and economic growth, calls for increased governance have also multiplied.

Some governance of the Internet, such as measures to make sure that Internet addresses are unique, and that changes to the root servers are conducted in a reliable and non-disruptive manner, is necessary merely to ensure that it operates smoothly and has already been in place for decades.[25]

In the early years of the Internet, this governance role was fulfilled by the U.S. government in a largely informal cooperation with academic experts. Since 1998, the U.S. government has contracted with the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) to manage most of the technical aspects of Internet governance. ICANN solicits input and feedback from the multi-stakeholder community, including Internet registries, registrars, businesses, civil society, and governments.

But a great contributing factor to the growth and success of the Internet, from which nearly everyone has benefited directly or indirectly, is that formal governance and regulation has been light and relatively non-intrusive. Indeed, the very light governance of the Internet and the resulting success raises the question of whether governments need to be involved in any substantial way in Internet governance.

Not all governments agree, however. Some, particularly governments eager to enhance their control over the Internet content and commerce, have repeatedly sought to assert international regulation and governance over the Internet far exceeding what is currently the case. The U.S. must work in concert with the broader Internet community—including businesses, civil society, registries, and registrars—to resist these efforts or risk crippling this enormously valuable catalyst for growth and communication.

Light Governance, Spectacular Growth

The relatively small number of Internet users and networks prior to the 1990s permitted a very informal and ad hoc approach to coordination and governance consisting of experts populating working groups, boards, and task forces established and tweaked as deemed necessary. An example of this informal approach was the fact that management of the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), that is, the allocation and recording of unique numerical addresses to computers called IP addresses that ensure that data is sent to the correct destination, was conducted by Dr. Jon Postel as a voluntary service from the early 1970s until his death in 1998.[26]

As the Internet grew in importance and use, more formal governance structures were developed. To facilitate policy decisions and manage the technical end of the Internet, the U.S. government supported the establishment of ICANN as a private nonprofit corporation in 1998 and contracted with it to undertake its current responsibilities. Along with managing the IANA functions, ICANN was charged with managing the Internet’s domain name system (DNS) and the system of global top-level domains (gTLDs), such as “.org,” “.com,” and “.gov.”

Since ICANN was created, it has been under contract with the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) to administer IANA. As noted by Harvard law professor Jack Goldsmith:

These oft-renewed contracts are why so many believe ICANN is controlled by the United States. Foreign governments resent this control because the top-level domain names are worth billions of dollars and have significant political and moral salience (think of .gay, or .islam). Control over domain names also entails the potential for censorship (by regulating domain name use on a global basis) that authoritarian states in particular find attractive.[27]

In reality, although the Commerce Department, through its contract with ICANN, has authority to review and reject ICANN policy and technical decisions, it very rarely has exercised this authority. By leaving Internet governance almost entirely to the private sector, the U.S. has allowed the Internet to grow and develop at a fantastic pace.

Imminent Change

While ICANN has been responsible for a large part of the technical details of running the DNS system, it works cooperatively with an American for-profit corporation, Verisign, which implements changes in the root zone file. This is essentially the core “address book” of the Internet. In addition, various technical constituencies, groupings, and organizations—some, such as the Internet Society and the Internet Engineering Task Force predate ICANN—exist independently of ICANN but participate in its deliberations and, like the Registrars Stakeholder Group, can in some instances play a role in selecting the ICANN board of directors. These various constituencies, groupings, and organizations along with the broader population of individual Internet users, businesses, and governments comprise the multi-stakeholder community whose bottom-up deliberations are to serve as the basis for ICANN decisions.

Although the U.S. has taken a very hands-off approach to ICANN, its contractual leverage arguably has helped ensure that ICANN pays due attention to issues and objections raised by the Internet community and adheres to processes as established in its bylaws and the Affirmation of Commitments with the Commerce Department. Since 1998, the Commerce Department has entered into contracts with ICANN to manage the IANA. These contracts have been periodically renewed with little controversy. However, the department always had the option of awarding the contract to an entity other than ICANN if it proved incompetent, unreliable, or otherwise unsatisfactory. The possibility that the Commerce Department could award the IANA contract to another organization, however unlikely, has provided an independent check on ICANN’s monopoly position.

This arrangement is about to change. In March 2014, the U.S. announced that it intended to end its oversight role over ICANN.[28] This announcement has energized debate over the next stage of Internet governance.

The Internet community has conducted detailed discussions inside and outside ICANN on how to enhance and ensure ICANN accountability, transparency, and reliability absent U.S. oversight.

At the same time, some governments have seen the U.S. decision to end its current relationship with ICANN as an opportunity to expand their influence over the Internet. China, Russia, and a number of Muslim countries[29] have sought for years to impose limits on online speech that they deem offensive or damaging to their interests.[30] These efforts have largely been blunted internationally, but have had far more success in individual nations. As noted by Freedom House in its Freedom on the Net 2014:

Global internet freedom declined for a fourth consecutive year…. New laws criminalized online dissent and legitimized overbroad surveillance and data collection, while more people were arrested for legitimate online activities than ever before.

“Authoritarian and democratic leaders alike believe the internet is ripe for regulation and passed laws that strengthen official powers to police online content,” said Sanja Kelly, project director for Freedom on the Net. “The scramble to legislate comes at the expense of user rights, as lawmakers deliberately or misguidedly neglect privacy protections and judicial oversight.” The situation is especially problematic in less democratic states where citizens have no avenues to challenge or appeal government’s actions.

“Countries are adopting laws that legitimize existing repression and effectively criminalize online dissent,” the report concludes. “More people are being arrested for their internet activity than ever before, online media outlets are increasingly pressured to censor themselves or face legal penalties, and private companies are facing new demands to comply with government requests for data or deletions.”

Freedom on the Net 2014 found 36 of the 65 countries assessed experienced a negative trajectory in internet freedom since May 2013, with major deteriorations in Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine.[31]

According to the 2014 Freedom House report, the worst abusers of Internet freedom were Iran, Syria, and China. Very few countries registered lasting policy improvements.

Indeed, governments are able to control Internet policies within their borders, albeit with varying degrees of success. Efforts to control Internet content globally, however, would be greatly facilitated by expanding government influence over the numbering, naming, and addressing functions of the Internet through enhanced authority over ICANN or the IANA directly through a stronger Governmental Advisory Council (an existing body that provides a forum for advice to ICANN by governments) or by placing it under the authority of an intergovernmental organization like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

This is not a new ambition for these nations and the U.S. has had to periodically rally opposition to similar efforts in the past. For instance, in the lead-up to the U.N. World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in 2003 and 2005, the U.N. Secretary-General established the Working Group on Internet Governance “to investigate and make proposals for action, as appropriate, on the governance of Internet by 2005” and to define Internet governance for the WSIS.[32] While the U.S. and other countries expressed support for the status quo, some nations called for granting the U.N. supervision of the Internet.[33]

As a result, this issue was deferred rather than resolved.[34] In the end, the WSIS adopted a generally positive, albeit imprecise, definition of Internet governance[35] that endorsed a role for the private sector and civil society—not just governments—and established the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) to bring together governments and nongovernmental entities to meet annually to hash out issues of concern and contention. Predictably, the IGF has struggled to bridge differences because key players fundamentally disagree over the role of states in Internet governance.

As such, the issue has arisen repeatedly in multiple forums since 2005. For instance, at the 2012 World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT), Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, and several other countries proposed that governments “shall have the sovereign right to establish and implement public policy, including international policy, on matters of Internet governance, and to regulate the national Internet segment, as well as the activities within their territory of operating agencies providing Internet access or carrying Internet traffic.”[36] These countries supported adopting new International Telecommunications Regulations (ITRs) that would grant the ITU authority over and responsibility for some of ICANN’s responsibilities.

Countries suspicious of ITU governance of the Internet took an equally strong position in opposition. Specifically, the U.S. stated, “[T]he United States will not support proposals that would increase the exercise of control over Internet governance or content. The United States will oppose efforts to broaden the scope of the ITRs to empower any censorship of content or impede the free flow of information and ideas.”[37]

The end result was division. After contentious negotiations, the U.S. and dozens of other countries announced that they could not support the proposed ITRs. In the end, only 89 countries, including many authoritarian regimes, such as Russia and China, signed the new ITRs.[38]

Unfortunately, the leaking of National Security Agency (NSA) surveillance in 2013 eroded the support that the U.S. had in these debates, despite the fact that NSA surveillance has nothing to do with the NTIA’s oversight of ICANN, and spurred renewed efforts to end U.S. oversight of ICANN.[39] The NTIA announcement of March 2014 temporarily blunted these calls. NETmundial’s Global Multistakeholder Meeting on the Future of Internet Governance in 2014 in Brazil, at which many countries were believed to be poised to call for U.N. oversight of the Internet, instead ended up endorsing the bottom-up, multi-stakeholder-driven model for Internet governance that the U.S. supports.[40] Similarly, the 2014 ITU Plenipotentiary Conference in Busan, South Korea, could have been a more lopsided replay of the WCIT, but ended up not adopting measures to extend ITU authority to cover the Internet, with a large number of countries endorsing the multi-stakeholder model for Internet governance.[41]

In essence, the debate is on hold until everyone can digest the results of the IANA stewardship and accountability transition proposals currently being developed by ICANN and the multi-stakeholder community. Once finalized, these proposals will be reviewed and approved by the multi-stakeholder community, the ICANN board of directors, and the NTIA.[42]

This effort is supposed to be finalized in summer 2015, but it is virtually certain that many governments will be dissatisfied with the results. After all, the NTIA must approve the final transition proposal, and its instructions are clear that the U.S. role should not be replaced by a “government-led or an inter-governmental organization solution.” Several upcoming and periodic events provide opportunities for renewed debate over Internet governance.

- The WSIS Forum provides an important opportunity for governments to voice support or opposition.

- The Commission on Science and Technology for Development (CSTD), a subsidiary body of the U.N. Economic and Social Council, is charged with serving as the focal point for U.N. follow-up of the WSIS and providing “the General Assembly and ECOSOC [Economic and Social Council] with high-level advice on relevant issues through analysis and appropriate policy recommendations or options in order to enable those organs to guide the future work of the United Nations, develop common policies and agree on appropriate actions.”[43] The CSTD, whose membership includes Russia, Cuba, China, Iran, and other states that have pressed for increased U.N. control of the Internet,[44] meets annually in May.

- The mandate of the Internet Governance Forum, established in 2005 at the WSIS and renewed in 2010, expires in 2015. The U.N. General Assembly is expected to renew the forum mandate, but potential exists for controversial additions regarding Internet governance, such as endorsing the proposal by China, Russia, and several central Asian nations to establish an “international code of conduct for information security.”[45]

- The ITU has adopted a number of resolutions on Internet-related issues, including governance, and governments dissatisfied with the IANA transition are likely to revive their agendas in the organization.[46]

- For instance, Resolution 102 adopted at the 2014 Plenipotentiary asserted that “all governments should have an equal role and responsibility for international Internet governance and for ensuring the stability, security and continuity of the existing Internet and its future development and of the future Internet” and resolved to “explore ways and means for greater collaboration and coordination between ITU and relevant organizations [including ICANN], involved in the development of IP-based networks and the future Internet, through cooperation agreements, as appropriate, in order to increase the role of ITU in Internet governance so as to ensure maximum benefits to the global community.” It also instructed the Secretary-General to “continue to take a significant role in international discussions and initiatives on the management of Internet domain names and addresses and other Internet resources within the mandate of ITU” and “take the necessary steps for ITU to continue to play a facilitating role in the coordination of international public policy issues pertaining to the Internet.”[47]

While these assertions are not necessarily incompatible with the IANA transition principles outlined by the NTIA, it clearly is a marker that the ITU continues to consider Internet governance within its remit to be addressed by the organization in future meetings.

Whether any of these venues adopt or endorse an increased role for governments in Internet governance depends in part on the success of ICANN and the multi-stakeholder community in drafting proposals that satisfy not only the broader Internet community and the NTIA, but enough governments around the world to ensure that a critical mass of countries that support increased government control over the Internet does not coalesce. Indeed, the generally acknowledged impetus behind the NTIA announcement was to forestall this very outcome. But other nations are not sitting idle, as illustrated by China hosting the first “World Internet Conference” that, among other things, sought support for increased control of content and respect for “Internet sovereignty.”

Conclusion

The future of Internet governance is at a crossroads. No system of Internet governance is perfect, including the current system, which many countries resent because of a perceived dominance by the U.S. However, the strong growth of the Internet in recent decades, and the economic growth resulting from that development, illustrate the virtues of the minimal governance model. The greatest risk to this successful model would arise from granting a more overt governance role to states either through the ITU or another intergovernmental organization, or by enhancing government authority within ICANN.

The March 2014 NTIA announcement clearly expresses the U.S. preference that governments and intergovernmental organizations should be relegated to a backseat role, following the lead of the private sector and civil society. Most of the private sector represented in the multi-stakeholder community supports this U.S. perspective on Internet governance. However, many powerful governments would prefer to exert tighter control of and oversight over the Internet. There are ample opportunities for countries that want more direct government control of the Internet to press their agenda.

It is unclear how this dispute will be resolved. But the stakes are high. If Internet functions and freedom are harmed or subjected to unnecessary regulatory burdens or political interference, not only would there be economic damage, but a vital forum for freedom of speech and political dissent would be compromised.

Brett D. Schaefer is Jay Kingham Senior Research Fellow in International Regulatory Affairs in the Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation, and editor of ConUNdrum: The Limits of the United Nations and the Search for Alternatives (Rowman and Littlefield, 2009).

Regulatory Barriers to Online Commerce

Michael Sargent PDF

It is difficult to overstate how radically the Internet has redefined the exchange of goods and services globally, and specifically within the United States, where users enjoy largely uninhibited access to the Internet. Shoppers from all across the globe can buy items and services to which they previously had no practical access—or indeed, even knew existed. The Internet makes this possible in a way that reduces transaction costs and makes markets transparent. The effect is a creative disruption of existing business models, to the benefit of consumers.

The changes in commerce created by the online revolution have frequently been met with opposition by entrenched interests that profited from the old system, and laws that long protected the status quo. While such barriers to online commerce have fallen in some areas, they still limit Web entrepreneurs and consumers in many others.

Removing existing barriers to e-commerce is especially important as online retail has become a consumer staple in the United States and has continued to experience rapid growth. Total annual online sales have increased tenfold since 2000 and grew at about 15 percent in 2014 alone.[48] While online retail still constitutes a relatively small share of overall retail activity, that share is growing. E-commerce accounted for only 0.6 percent of total retail in 1999, but today e-commerce sales have grown to almost 7 percent of total retail sales.[49]

Online commerce has flourished in the United States in large part because the government has taken a light touch regulatory approach toward the Internet. However, state-level regulations continue to place hurdles in the path of e-commerce.

These laws have various origins. Some are no doubt well intentioned. Others were specifically intended to limit new competition that would challenge incumbent players in the marketplace. Such limits include many laws adopted before the Internet was even imagined, as well as some adopted to ward off perceived threats from Internet-based competitors. Whatever the origins, these laws impose real costs on consumers, depriving them of the full benefits that Internet technology can provide.

The following illustrates how such rules have harmed consumers in three different markets:

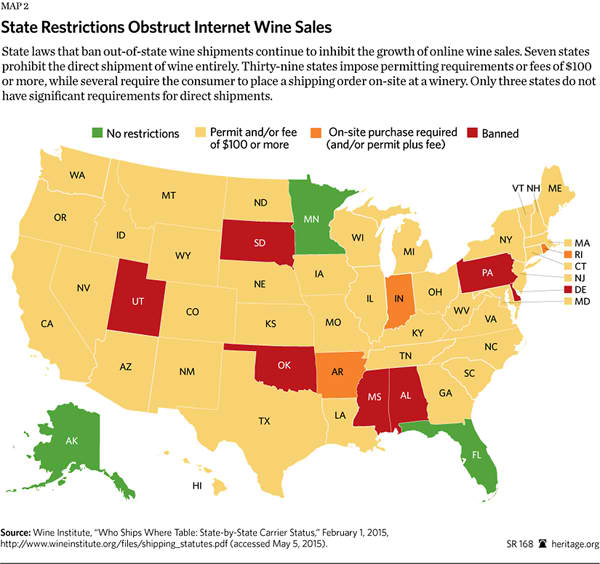

Online Wine Shopping and Delivery

Internet-based sales of wine were severely limited due to a long-standing labyrinth of state and local laws limiting the interstate shipment of wine. These laws varied in their coverage, but effectively curtailed challenges to in-state distributors by Internet-based sellers, as well as mail-order sellers. The rules were so restrictive that, as during the Prohibition era, many modern-day vintners turned to bootlegging to sell their product.[50]

According to a 2003 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) study, these bans hurt consumers. In particular, the variety of wines available online was 15 percent greater than the local selection, and was available at up to a 20 percent discount compared to local prices.[51] The FTC noted that statewide bans on direct shipping of wine to consumers were the largest barrier facing the industry, but also observed myriad other regulations, including:

[P]rohibitions on online orders, very low ceilings on annual purchases, bans on advertising from out-of-state suppliers, requirements that individual consumers purchase “connoisseurs’ permits,” and requirements that delivery companies obtain a special individual license for every vehicle that might be used to deliver wine.[52]

A great deal of progress has been made since 2003 as states have overhauled their shipping rules to allow online purchase and shipping of wine. This trend was spurred by a 2005 Supreme Court ruling prohibiting states from discriminating against wine shipped from another state.[53] To some extent, this relaxation of rules has upended Prohibition-era laws in many states that banned producers from selling their product directly to consumers. However, many problems remain. The direct shipment of wine[54] is still prohibited (with some exceptions) in seven states: Alabama, Delaware, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Utah. These states would do well for their residents to remove laws that artificially limit selection and increase prices for consumers.

Various problems also continue even in states that allow direct shipments by online wine distributors. Many states require out-of-state wineries to obtain permits or licenses in order to ship to customers in their states.[55] Massachusetts, which just authorized direct wine shipments in January 2015, requires that both the producing vintner and each vehicle transporting the wine obtain a permit from the state.[56] Furthermore, some states, such as Rhode Island, require the consumer to conduct the purchase onsite at the vintner’s, thus eliminating the convenience of ordering wine online. When this burden is multiplied across multiple states, permitting requirements and other restrictions create significant barriers to commerce.

Other regulations plague even the largest online distributors. Wine.com, the leading online retailer, spent $2 million for regulatory compliance in 2012, compared to total revenues of $80 million.[57] The retailer has faced fines from the State of New York for seemingly innocuous violations of state laws such as shipping bottles of wine with food in gift baskets. (New York law requires that alcohol be shipped separately from food.) In addition, the retailer had to build seven separate warehouses to comply with various state laws and regulations.[58]

While state and local governments often have good intentions and justification for passing frivolous-sounding laws to protect consumers, the overall effect of these laws is to harm consumers’ choice and purchasing power.

Direct Automobile Sales

The Internet has given users unprecedented access to customizable goods and services. Users order exactly what they want, from new clothing to a new home. Yet there is one major life purchase that cannot be made online: a new car.

Given the customizability of today’s autos, it should be easy to pick a make and model online and then buy it directly from the manufacturer. But such direct sales are now banned in 47 states. These bans, specifically intended to protect local dealers from competition from out-of-state carmakers, date back to the early 20th century. It is only one of many rules imposed on behalf of dealers, who have long exercised outsized influence with local lawmakers.[59]

But whatever their ostensible justification at the time, today, in a time of globalization and intense competition in the auto market, these regulations simply ensure that dealers remain the middlemen between manufacturers and consumers. Instead of being able to design a built-to-order car online and order it straight from a manufacturer, new car customers have to physically visit a dealership and haggle with a salesman. This arrangement ignores the increasing trend of consumer preference for online shopping—even for cars. In 2014, consulting firm Capgemini found that 34 percent of American car buyers would be likely or very likely to purchase a car online (opposed to researching online and buying at a dealer[60])—up from 25 percent just a year before.[61] Even worse, the regulation comes at the expense of the consumer: One study estimates that the dealer requirement adds $2,000 to the sticker price of a new automobile.[62]

Allowing consumers to buy cars directly from manufacturers who sell online—rather than through a dealer who merely resells cars as a middleman—would give them greater access to customizability, efficiency, and choice. Manufacturers would be able to distribute and ship cars from one or few locations to anywhere in the country, as opposed to shipping first to hundreds or thousands of dealerships.[63]

Recognizing the potential of direct online car sales to benefit consumers, the automaker Tesla—a newcomer to the auto manufacturing market—is trying to overcome these state restrictions and sell online directly to consumers. Tesla has had some victories: The company recently won legislative battles in Nevada, Georgia, and New Jersey that will allow it to engage in direct sales. A court decision in Massachusetts has paved the way for direct sales in that state as well.[64]

But aside from these recent successes for Tesla and consumers, regulations and protectionism have prevailed. Most states still have legislative bans on direct sales, and Michigan, under pressure from the dealers’ lobby, even enacted a specific bill that strengthened the ban of direct-to-consumer sales just as Tesla was about to expand in the state.[65] Even in Georgia, where Tesla recently scored a relative victory when the State House of Representatives voted to lift the 150-vehicle limit for direct sales, the state still imposes a limit on the number of Tesla dealerships the maker is allowed to establish, currently capped at five.[66] Similarly, New Jersey’s law limits Tesla to four dealerships statewide.[67]

This protectionism is indefensible from an economic and consumer-welfare standpoint. As John Kerr, a communications fellow at the Institute for Justice, pointed out in The Wall Street Journal:

There is no rational reason Tesla—or any other automobile manufacturer—should be restricted from selling new cars directly to those who seek to buy them. Arguments that franchise arrangements benefit consumers ignore not only the higher costs inherent in regulations that limit choice, but the benefits of a vibrant and responsive market in which new-car buyers are free to avail themselves of multiple purchasing options.[68]

Indeed, even General Motors, America’s largest automaker, has realized the benefits of this superior business model. Recently, the entrenched firm invested in 8,000 software programmers to develop its “shop-click-drive” website, which enables users to choose and purchase a car online.[69] But there’s a catch: The transaction must still be completed through a GM dealer and the dealer’s own website. In addition to the inherent difficulties of developing an online experience as complex as GM’s, routing it through various dealership websites made the whole process “difficult” according to a GM spokeswoman. Indeed, GM’s shop-click-drive manager Jim Bement acknowledged that “[t]here is no way a dealer could do something like this on his own,” begging the question of why dealers should be involved in a transaction that could otherwise be completed directly between the consumer and the automaker.

The “Sharing Economy”

The rise of cheap mobile phones and data programs has allowed a variety of platforms to connect people in direct peer-to-peer networks, enabling a more efficient exchange of goods and services. Dubbed the “sharing economy,” online applications, such as ridesharing services (Lyft, Sidecar, or Uber) or apartment sharing (Airbnb) have revolutionized industries by linking users directly to individuals who provide the requested service, such as a car ride, via the Internet.

These new “sharing” businesses, made possible by the Internet, do not fit neatly into any existing regulatory categories. Should they be treated as commercial hotels and taxicabs, or more like an individual who sublets his apartment or gives occasional rides to others? The business categories blur the existing lines, and that is precisely what makes them so difficult to pigeonhole. “We’ve lived in a world where there was this clear line between picking your friend up at the airport—you clearly don’t need a permit for that—or lending your apartment to a cousin when he or she or visits, and running a hotel,” says New York University’s Arun Sundararajan. “It’s important to recognize that these lines are blurring.”[70]

Incumbent players have fought these new enterprises at every turn. Taxi cab monopolies in major cities attempted to ban ridesharing services outright or subject them to the same artificial restrictions and price regulation imposed on taxis.[71] The hotel industry has fought Airbnb, pushing to subject it to the full panoply of hotel rules.[72]

Again, these rules are often imposed under the guise of consumer protection, but the regulations benefit entrenched firms, raise consumer prices, and squash innovation. As Heritage Foundation legal scholars Jason Snead and Paul J. Larkin, Jr., note, the practice of using regulatory clout to bankrupt competitors is not only wrong, but will hurt American ingenuity in the long run:

The only sure way to keep markets open to the next Uber-like innovator is to get the government out of the business of picking winners and criminalizing competition. Not only does government generally do a poor job of it, but entrepreneurial success in America should not be dependent on political connection and favoritism. Nor should new competitors be threatened with costly court battles in every market they try to enter.[73]

Rather than blindly applying existing rules to these new forms of commerce, policymakers should carefully reconsider whether those rules still make sense, and whether they make sense for new business forms. Thanks to the new challengers, for instance, there are now more choices and more competition among taxi services than ever before. Why are government price controls necessary in this new competitive environment? Other rules, such as permits, may also not make sense for the “sharing” business. The effect without rules will be a disruption of the existing marketplace, and that is a plus, not a minus for consumers and entrepreneurs. The Internet has made these new forms of economic and consumer freedom possible; these benefits should not be dismissed due to fear of change.

Conclusion

The Internet has radically redefined commerce by decreasing transaction costs of selling almost anything that can be imagined, all to the great benefit of both vendors and buyers. Yet impediments remain due to outdated regulation and laws designed to benefit politically connected middlemen. In this case, the states—not the federal government—are the leading offenders. Freeing online enterprises from these rules will not only benefit entrepreneurs, it will also allow innovation to flourish, advance consumer welfare, and bolster economic freedom.

Michael Sargent is a Research Assistant in the Thomas A. Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.

Protecting Internet Commerce from Undue Tax Burdens

Curtis S. Dubay PDF

The Internet is facing two threats from lawmakers in Washington that could hamper its ongoing development and raise taxes on Americans already struggling under a hefty tax burden.

The first threat is proposed legislation that would allow states to require out-of-state retailers to collect sales taxes on online purchases even if the retailer has no physical presence in the buyer’s home state. The potential of expanding the sales tax to these sales is often referred to as an “Internet sales tax,” since the bulk of such out-of-state sales are made online.

The second threat comes in the form of Congress allowing states to tax mere access to the Internet, a tax on which it placed a moratorium in 1998.

In the case of both threats, it would be best for Congress to continue its long-standing policies to avoid placing unnecessary burdens on the Internet, as well as protect American taxpayers from higher taxes.

Background

Currently, states can only collect sales taxes on purchases their residents make online if the retailer has a physical presence in the state. A store, workforce, factory, storage facility, building, or employees in a state usually establish a physical presence.

The physical-presence standard was established by the 1992 Supreme Court decision in Quill v. North Dakota.[74] It applies to all remote sales, which include online sales as well as mail order and catalog sales.

The standard has come under pressure because state legislatures, and state tax collectors, are increasingly frustrated by not being able to collect sales taxes on some online sales that they believe they should be able to tax. They see online sales as eroding their sales-tax base.

Adding to the pressure to overturn the standard are “brick-and-mortar” retailers. These traditional sellers see the current situation as unfair because, they argue, it hurts their ability to compete. They must collect the sales tax on all their sales. If a customer buys an identical product online from a retailer with no physical presence in the customer’s state of residence, the customer does not have to pay the applicable sales tax, lowering the price he pays by the amount of the sales tax.

Online sellers that have substantial physical presence also want to see online sales taxed. Because they are physically present in many states, they are already collecting taxes on many of their sales. Similar to brick-and-mortar sellers, they want to put the added burden of collecting sales tax on their smaller competitors.

These groups have put strong pressure on Congress to change the physical-presence standard, something the Supreme Court gave it power to do in its Quill decision. They have found significant sympathy for their position in Congress because, theoretically, a consumer should pay the same tax on an item regardless of whether he purchases it at a store or online. But meeting that theoretical standard has proven problematic in the legislative solutions that have been proposed.

Recent Bills in Congress

In 2014, the Senate passed the Marketplace Fairness Act (MFA) to address online sales taxes. The MFA would have allowed states to enforce their sales tax on out-of-state online retailers if those states had more than $1 million in sales. This posed two major problems. First, it would have violated the principle of federalism by allowing states to enforce their sales tax laws outside their borders. Second, it would have imposed an enormous burden on smaller online sellers. There are close to 10,000 sales tax jurisdictions in the U.S. because localities, in addition to states, levy the tax. Online retailers would have been responsible for knowing the rate, base, and other rules and regulations for each of those jurisdictions so they could have collected the appropriate amount of tax from their customers and return those collections to the right locale. Because of these flaws, and others, the House did not take up the MFA.[75]

In early 2015, Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee Bob Goodlatte (R–VA) released a different plan known as “home rule and revenue return.”[76] Under this plan, retailers would collect sales tax on sales to out-of-state customers based on the sales tax law in the business’s home state, if their state joins an inter-state agreement. This would reduce the burden that the MFA would have placed on online retailers, since they would not be responsible for knowing the sales tax laws of nearly 10,000 jurisdictions. However, the plan would force online businesses in the four states that do not have a sales tax (Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon) to collect a minimum sales tax, or to report the name and address of the buyer to their home state tax authority. In effect, it would create a federal sales tax that online businesses in these states would have to collect. This, despite the fact that these no-sales-tax states have expressly chosen not to place the burden of collecting a sales tax on their businesses. Such a federal obligation represents a dangerous extension of the reach of state tax collectors.[77]

Proposals Have Not Been Able to Thread the Needle

A top-down policy from Washington that raises taxes on customers and burdens retailers could curtail the growth of the Internet as an engine of economic growth and set a dangerous precedent that expands the taxing power of states. The failure of recent proposals to find an adequate solution is strong evidence that the best approach to solving this perceived problem is to maintain the policy that has been in place for 23 years—the physical-presence standard. It has held up remarkably well for a standard that was set before the Internet became an ever-present part of daily life.

This standard has withstood the test of time in large part because the biggest online retailers have a growing physical presence around the country. As such, sales taxes already apply to a significant portion of online purchases. According to one recent survey, half of all consumers said they paid sales taxes on their most recent online purchase.[78] Using 2008 data, one study found that 17 of the 20 largest online sellers—ranging from Office Depot to Apple—had retail stores or other facilities nationwide, and collected taxes in all or almost all 46 states that impose sales taxes.[79] These data do not include recent steps by Amazon and other online sellers to expand their physical operations to meet ever-shorter shipping timelines demanded by their customers. This trend, if continued, could solve the dilemma on its own.[80]

Taxing Internet Access

The moratorium on state and local government taxation of Internet access and other Internet services, such as e-mail and instant messaging, or a direct tax on “bits,” has been in place for 17 years now, but has been set to expire periodically. The last time the moratorium was scheduled to expire was in December 2014, when Congress extended it until the end of 2015. The ever-present threat of its expiration is disrupting to consumers and the economy. It is time for Congress to make the moratorium permanent.[81]

If states were allowed to levy these taxes, they could greatly reduce access to Internet services by raising the price for consumers. According to a study by economist George Ford of the Phoenix Center, even a relatively low average tax of 2.5 percent could reduce broadband subscribership by five million to 15 million people, compared to what it would otherwise be. If state taxes average 5 percent, the loss could total between a whopping 10 million and 30 million subscribers.[82]

Entrepreneurs and businesses that rely on the Internet also need the certainty that permanency provides. The prospect of higher taxation makes businesses less willing to invest, and makes it harder for would-be entrepreneurs to go into business.

The drag on the economy of this uncertainty is not trivial. Of the 25 firms investing the most in the U.S. economy, 11 are in Internet-related businesses—including the two largest, AT&T and Verizon, who invested nearly $35 billion in 2013.[83]

There are concerns among some that a permanent ban on state taxes would violate the principle of federalism. However, the Internet is undoubtedly part of interstate commerce, and it is therefore well within Congress’s power to apply a ban on taxing it.

Congress will soon have the opportunity to ban taxes on Internet access and activities permanently. It should do so.

Curtis S. Dubay is Research Fellow in Tax Policy in the Thomas A. Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.

Copyright and the Internet: Getting the Balance Right

Alden F. Abbott PDF

The ability to create without undue fear that one’s creation will be appropriated by others without consent is a fundamental freedom, whether that creation is tangible or intellectual in nature. Overly burdensome rules limiting legitimate rights to use and transmit ideas limit freedom. Balancing these two freedoms has long been a challenge in the law, and the explosive growth of the Internet has made that job much harder. The sale of counterfeit goods, including tangible items, such as branded clothing and pharmaceuticals—as well as the illegal sale of digital goods, such as music and Hollywood movies—has proliferated on the Internet. Such activity is a form of theft, and the federal government has a legitimate role in preventing it.

The unauthorized downloading of copyrighted writings, designs, artwork, music, and films lowers revenue streams for artists and reduces their incentives to create new works, and limits their ability to enjoy the fruits of their labors. A key question for policymakers is how to best protect the creators of intellectual property without harming growth and innovation in Internet services or vital protections for free speech.

Copyright Issues

Federal copyright-law protection extends to literary, musical, and artistic “original works of authorship.” [84] U.S. law gives the copyright owner the exclusive rights to reproduce, sell, rent, lease, distribute, display, and publicly perform the copyrighted work, and to prepare derivative works based upon the work.[85]

Thanks to the Internet, both the legitimate and illegitimate distribution of such works has become far easier. A 2013 U.S. Department of Commerce task force report on copyright in the digital economy noted that the Internet “has given consumers unprecedented tools to reproduce, alter and immediately transmit perfect digital copies of copyrighted works around the world, and has led to the rise of services designed to provide these tools.”[86] Those tools include, for example, peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing services and mobile apps designed to foster infringement. Many websites that provide pirated content—including, for example, online video-streaming sites—are located outside the United States.

Copyright infringement “has resulted in billions of dollars in losses to the U.S. economy—including reduced income for creators and other participants in copyright-intensive industries.”[87] Those losses are felt by the full spectrum of content industries, including music, motion pictures, television, visual arts, and software.[88]

Current federal law provides a variety of tools to combat such infringement. Both the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) are authorized to take civil and criminal enforcement actions against infringers, including seizing property used in connection with infringement. However, jurisdictional limitations that restrict seizures to Internet domain names registered with a U.S. registry limit the effectiveness of these efforts. Criminal enforcement may also have an international dimension, with DOJ investigations assisted by foreign law enforcers.[89]

Copyright holders have a number of litigation tools to defend their interests. The first tool involves lawsuits against “primary infringers”—parties who directly violate others’ copyrights. Suits against individual file sharers have proven rather ineffective, however, given the large number of such direct infringers and the difficulty in identifying them and bringing them to court. Direct infringement suits against ISPs are difficult, since infringement requires “some element of volition or causation,” and ISPs typically are not directly complicit in copyright pirates’ decisions to place materials online.

The second tool involves lawsuits against “secondary infringers”—parties who facilitate direct infringers’ violations of copyrights. In recent years, claims of secondary liability against online intermediaries have become increasingly important. Such claims have been brought successfully against P2P file-sharing services, such as Napster and Grokster, and against other types of online services, including video-hosting sites, BitTorrent sites, Usenet.com (a worldwide discussion board), and “cyberlockers” (which allow users to store and share large files).[90]

In addition, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)[91] establishes various extrajudicial tools to combat infringement.[92] Although it creates liability-free “safe harbors” for ISPs when engaged in specified activities (serving as a mere conduit to transmit content, or providing caching, hosting, or information tools), the DMCA requires ISPs, in turn, to block or remove infringing content for which they have received a valid notice or are otherwise aware. A “put-back” mechanism empowers ISPs to restore content that was removed by mistake or due to misidentification. This structure has generated a widely used extrajudicial tool—“notice and takedown”—for curbing infringement.

Potential New Tools

A variety of new potential tools have been proposed to augment these existing copyright enforcement mechanisms.[93] These include website blocking (directing ISPs to block access to websites dedicated to piracy), content filtering (screening incoming network traffic for signs of infringement), “following the money” (requiring payment processors and online advertisers to cut off funding of infringers), and restrictions on the types of links that search engines are allowed to display.

Many of these approaches were proposed in 2011 in the Stop Online Piracy Now (SOPA) and Protect Intellectual Piracy Act (PIPA) bills. But the proposed legislations raised a number of concerns. For instance, requiring search engines to omit links to rogue sites undercuts the role of search firms as trusted intermediaries in conveying information to users. Arguably, such limits would violate constitutional protections of freedom of speech. Even if constitutionally permissible, such a mandate would represent a step on a classic slippery slope of government interference that has no clear stopping point.[94]

Ill-considered mandates could also compromise security by blocking “resolution” of IP addresses by servers in the U.S., causing users (and their browsers) to rely instead on less secure servers elsewhere to access blocked sites.[95]

Some approaches do not require state action for implementation. For example, in 2011 a coalition of major ISPs and industry associations agreed to a voluntary “Copyright Alert System,” which establishes a process for handling repeat infringing activity by online users of P2P file-sharing networks, short of account termination. This agreement, which is being implemented by the Center for Copyright Information (CCI), began operating in 2013.[96] Specifically, the CCI administers an alert system under which ISP subscribers are notified when they initially access infringing materials, and are subjected to a series of graduated sanctions from warnings to ISP service downgrades of varying severity if they persist in their behavior (disputes under this system are subject to independent review and arbitration).[97]

There are other ways in which private, voluntary efforts can alleviate infringement problems. For instance, new technologies allow websites that contain licensed content to be marked and highlighted for consumers, enabling them to better identify legal services that are available online, and diminishing incentives to access infringing materials.[98] In addition, services that make online content more easily available to consumers can significantly reduce demand for pirated materials. These services, the biggest of which is iTunes, are quite successful in the music world, and video-download services, such as Apple TV and Amazon Video, are growing rapidly among movie watchers.

Conclusion

A variety of approaches—many of which are private, voluntary initiatives requiring no new laws or regulations—have been deployed to combat online copyright infringement, and new ones are being developed. While these efforts have not eliminated infringement, which remains a substantial problem,[99] they are having some success.

There is no “silver bullet.” Curtailing online infringement will require a combination of litigation tools, technology, enhanced private-sector initiatives, public education, and continuing development of readily accessible and legally available content offerings.[100] As the Internet continues to develop, the best approach to protecting copyright in the online environment is to rely on existing legal tools, enhanced cooperation among Internet stakeholders, and business innovations that lessen incentives to infringe.

Alden F. Abbott is Deputy Director of the Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies, and John, Barbara, and Victoria Rumpel Senior Legal Fellow, at The Heritage Foundation.

The Intersection of Internet Freedom and Cybersecurity

David Inserra PDF

Freedom requires that one be safe and secure in one’s possessions—a world in which criminals steal or destroy one’s property at will is neither free nor secure. The same is true in cyberspace, where digital criminals have a great interest in stealing sensitive data or disrupting critical services. And with everything from military systems to smartphones now linked to the Internet, the number of bad actors seeking to attack or steal from those targets has increased dramatically. Hackers compromise, steal, or destroy hundreds of billions of dollars in intellectual property and real money every year, as well as accessing critical military secrets from the United States. While different estimates exist for the cost of cybercrime, they seem to point to annual costs to the U.S. of $100 billion or more, and to global costs that could reach $600 billion.[101]

Regulatory Solution Falls Short

How can this problem be addressed? Early congressional proposals supported by the Obama Administration would have imposed mandatory cybersecurity standards on key private-sector industries.[102] Mandatory standards have certain surface appeal: After all, if security standards in the private sector are not where they should be, shouldn’t the government step in and require better security? While simple in theory, this approach actually has several fatal flaws.

First, regulations will have a hard time keeping up with the rapidly changing environment. Moore’s Law states that the processing power of computers will double approximately every two years—a law that has been true since the 1970s. While cyber mandates may be able to improve cybersecurity by making companies able to address threats of the last generation, they are ill prepared to address constantly changing threats that emerge from the current and future generations of technology.

Second, because of the delay inherent in government regulation, cybersecurity innovation suffers. Even if proposed regulatory proposals avoid proscribing specific solutions, they tend to focus on problems, threats, and features of cyberspace that are specific to the past. As a result, companies will seek solutions that meet the outdated regulations, at the expense of solutions for the current or foreseeable crop of problems. Thus, government regulation could actually weaken U.S. cybersecurity.[103]

Third, regulations often create a culture of compliance. Regulations ultimately require businesses to do certain things or face penalties. When faced with such prospects, many companies will seek the lowest-cost way of meeting these standards, regardless of whether such actions will be the best decision for any given company. This compliance-over-security mindset opposes innovation and real engagement with the issue at hand. As a result, regulations are a less than ideal way to encourage cost-effective investments in security.

Engaging the Private Sector

Policymakers can reduce barriers to improved cybersecurity by using private-sector incentives instead of top-down mandates. One is the sharing of cybersecurity threat and vulnerability information among both private and public-sector entities. By sharing information, different entities in the two sectors can be warned about likely attacks or other specific problems. No company or government agency knows everything about cybersecurity, which makes sharing information about threats and vulnerabilities a cost-effective way to raise cyber preparedness and awareness. Information sharing can be seen as a kind of crowdsourcing function, akin to the popular “Waze” application for traffic data, by which users voluntarily report traffic conditions they experience. Just as Waze helps large numbers of individuals on their commute, information sharing in cyberspace helps businesses and government agencies avoid cybersecurity potholes and problems, and does so at little cost.

Information sharing is a relatively inexpensive way of improving cybersecurity and it involves minimal sharing of personal information. While sensitive and personal data in e-mails and databases may be the target of cyberattacks, information sharing is not aimed at using the personal content of those e-mails and databases since that information does nothing to support security. Instead, sharing information about threats, vulnerabilities, and the source of attacks enhances and protects the privacy of Internet users.

Enabling Better Information Sharing

There are, however, a number of government-imposed obstacles that are impeding voluntary sharing of information. Policymakers should remove these obstacles by: